The problem of all corporate employees is monotonous workload, which leads to loss of strength and physical ailments. To avoid them and achieve heights in your profession, you need to learn how to manage your internal energy. The principles and techniques described in the book will teach you to work effectively under pressure, find hidden sources of energy within yourself and maintain excellent physical, emotional and mental shape.

For anyone who works hard, sets professional and personal goals, and strives every day to achieve them.

Preface

Cure for downshifting

Many have been waiting for this book for a long time. They waited, not yet suspecting its existence, title or authors. They waited, leaving the office with a greenish face, drinking liters of coffee in the morning, not finding the strength to take on the next priority task, struggling with depression and despondency.

And finally they waited. There were specialists who gave a convincing, detailed and practical answer to the question of how to manage the level of personal energy. Moreover, in various aspects - physical, intellectual, spiritual... What is especially valuable are practitioners who have trained leading American athletes, FBI special forces and top managers of Fortune 500 companies.

Admit it, reader, when you came across another article about downshifting, the thought probably crossed your mind: “Maybe I should give up everything and go somewhere to Goa or a hut in the Siberian taiga?..” The desire to give up everything and send everyone to any of the short and succinct Russian words is a sure sign of lack of energy.

The problem of energy management is one of the key ones in self-management. One of the participants in the Russian Time Management community once came up with the formula “T1ME” management - from the words “time, information, money, energy”: “time, information, money, energy.” Each of these four resources is critical to personal effectiveness, success and development. And if there is quite a lot of literature on time, money and information management, then in the field of energy management there was a clear gap. Which is finally starting to fill up.

Part one

Full Power Driving Forces

1. At full power

The most precious resource is energy, not time

We live in a digital age. We are running at full speed, our rhythms are accelerating, our days are cut into bytes and bits. We prefer breadth to depth and quick response to thoughtful decisions. We glide across the surface, ending up in dozens of places for a few minutes, but never staying anywhere for long. We fly through life without pausing to think about who we really want to become. We are connected, but we are disconnected.

Most of us are just trying to do the best we can. When demands exceed our capabilities, we make decisions that help us break through the web of problems but eat up our time. We sleep little, eat on the go, fuel ourselves with caffeine and calm ourselves down with alcohol and sleeping pills. Faced with unrelenting demands at work, we become irritable and our attention is easily distracted. After a long day of work, we return home completely exhausted and perceive family not as a source of joy and restoration, but as just another problem.

We have surrounded ourselves with diaries and task lists, handhelds and smartphones, instant messaging systems and “reminders” on computers. We believe this should help us manage our time better. We pride ourselves on our ability to multitask, and we demonstrate our willingness to work from dawn to dusk everywhere, like a medal for bravery. The term “24/7” describes a world where work never ends. We use the words “obsession” and “madness” not to describe madness, but to talk about the past working day. Feeling that there will never be enough time, we try to pack as many things as possible into each day. But even the most effective time management does not guarantee that we will have enough energy to get everything done.

Are you familiar with such situations?

– You are in an important four-hour meeting where not a second is wasted. But the last two hours you spend the rest of your energy only on fruitless attempts to concentrate;

Living laboratory

The idea of the importance of energy first came to us in the “living laboratory” of professional sports. For thirty years, our organization has worked with world-class athletes to determine what allows some of them to perform at their best over the long term under constant competitive pressure. Our first clients were tennis players - more than eighty of the world's best players such as Pete Sampras, Jim Courier, Arancha Sanchez-Vicario, Sergi Brugueira, Gabriela Sabatini and Monica Seles.

They usually came to us at the moments of the most intense struggle, and our intervention often led to the most serious results. After our work, Arancha Sanchez-Vicario won the U.S. for the first time. Open

Then athletes from other sports began to come to us - golfers Mark O'Mira and Ernie Els, hockey players Eric Lindros and Mike Richter, boxer Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini, basketball players Nick Anderson and Grant Hill, speed skater Dan Jensen, who won the only his life's Olympic gold medal only after two years of intensive training with us.

What made our method unique was that we did not spend a second studying the technical or tactical skills of our players. The common cliché is that if you find a talented person and teach him the right skills, he will produce the best results. But in practice this happens very rarely. It turns out that energy is the unobvious factor that allows you to “ignite” talent to its full potential. We never wondered how Seles hits the ball on a serve, how Lindros flicks the puck, or how Hill shoots free throws. They were all extremely gifted before they came to us. Instead, we focused on helping them learn to manage their own energy to accomplish whatever task they were faced with.

Athletes have proven to be very demanding experimental subjects. They were not at all satisfied with “uplifting” conversations or sophisticated theories. They were interested in measurable and lasting results - the number of aces

As word of our success in sports began to spread, we began to receive numerous offers to “export” our model to other areas of human activity that require high impact. We worked with FBI hostage teams, marshals, and emergency medical technicians. Nowadays, the bulk of our work is related to business - with CEOs and entrepreneurs, managers and salespeople, and more recently, also with teachers and officials, lawyers and medical students. Our corporate clients include Fortune 500 companies such as PepsiCo, Estee Lauder, Pfizer, Brisol-Myers Squibb, Hyatt Corporation and many others.

Change process

How to put all this into practice? How to generate and retain all the necessary types of energy - especially when the demands on us increase, and our capabilities decrease with age?

We've found that the changes that produce the most lasting results must be based on a three-step process we call "Define the Goal - Face the Truth - Take Action." All stages are necessary, and none is sufficient alone.

The first step of our change process is “Define the Purpose.” In the face of our habits and our instinct to maintain the status quo, we need passion to change our lives. Our first challenge is to answer the question, “How do I spend my energy in a way that aligns with my true values?” One of the consequences of living at breakneck speeds is that we don't have time to reflect on what we value most and keep it our focus. We typically spend more time reacting quickly to sudden crises and meeting the expectations of others than making thoughtful choices guided by a clear understanding of what is most significant in our lives.

At the goal definition stage, you need to identify and formulate the most important values in your life and characterize their image - personal and professional. Commitment to values and creating a compelling image provide the “high octane fuel” for change. They also give us a rudder and a compass to navigate the storms that inevitably accompany our lives.

You can't chart a course of change until you take an honest look at yourself. In the next stage of our process - "Face the Truth" - the first question we need to ask ourselves is: "How are you currently using your energy?" Each of us is a master at avoiding unpleasant truths about ourselves. We constantly underestimate the consequences of our energy management decisions: by not recognizing the harm in the foods we eat; allowing yourself excess alcohol; not investing enough energy in relationships with bosses, colleagues, spouses and children; without concentrating on your work. Too often we view our lives through rose-colored glasses, see ourselves as victims of circumstance, or refuse to recognize the connection of our choices to the quantity, quality, strength, and focus of our energy.

Remember

– Managing energy, not time, is the key to high performance. Productivity is based on skillful energy management.

– Great leaders are conduits of organizational energy. They start by managing their own energy effectively. As leaders, they must mobilize, focus, invest, direct, renew and expand the energy of their employees.

– Full power is the level of energy that allows you to achieve the highest efficiency.

– Principle #1: Full power requires the connection of four interconnected sources of energy: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual.

– Principle #2: Because our energy capacity is reduced by both overuse and underuse of energy, we must maintain a balance between energy expenditure and energy storage.

2. The Life of Roger B

Power Loss

When we first met Roger B., his life seemed completely successful. He was forty-two years old and was a sales manager at a large software company. His salary exceeded one hundred thousand dollars a year, he was responsible for sales in four states on the West Coast, and a year and a half ago he was promoted to vice president - this was his fourth promotion in five years. His wife Rachel was thirty-nine. They met in college, married about fifteen years ago, and had two daughters, nine-year-old Alice and seven-year-old Isabel. Rachel worked very successfully as a school psychologist. They lived in a suburb of Phoenix, surrounded by families like them, in a house they had designed themselves. Their lives were filled with their own careers and raising two children. They have done a lot to achieve just such a life. At first glance, no problems were noticeable.

However, we already knew that Roger's boss was increasingly dissatisfied with his performance at work. “We considered him a rising star for many years,” he told us. “I can’t imagine what happened to him.” Two years ago we promoted him to an important leadership position, but during that time his productivity dropped from an A to a C+. And it has an impact on his entire team.

I'm very disappointed and upset. I haven't lost hope yet, but if something doesn't change soon, we'll have to break up. I would be very glad if you could help him improve the situation. He is a good and talented person. I wouldn’t like to part with him.”

The most important part of our work process is to try to look “beneath the surface” of the life that a person leads. Facing the Truth begins with completing a detailed questionnaire designed to identify a person's behavioral patterns and measure the efficiency of how they spend and recover all types of energy of interest to us. In addition, Roger wrote a short report on his health and nutritional patterns. When he came to us, we performed several tests on his physical condition, which included an assessment of his cardiovascular system, strength, flexibility, signs of obesity, and several blood tests, including cholesterol levels. Of course, you won't be able to get the same data about your physical condition by reading this book, but we can say for sure that if you don't do regular cardiovascular and muscular training like the ones we describe in Chapter 3, you will almost You are probably losing the capacity of your energy system.

Feedback from colleagues about Roger indicated that there were five main barriers to high performance: low energy, impatience, negative attitude, lack of depth in relationships, and lack of enthusiasm. His self-esteem wasn't much better. All of the barriers we found have a common cause: poor energy management, whether in the form of insufficient energy recovery, insufficient reserve capacity, or, more typically, both. Moreover, each of these barriers almost always depends not on one, but on many factors.

The foundation is physical energy

In Roger's case, the most important factor in creating barriers was the way he managed his physical energy. He was an athlete in both college and university. He played basketball and tennis and always took pride in his physical fitness. While filling out our medical questionnaires, he noted that he was 2–3 kilograms overweight, but when answering another question, he admitted that he had gained more than 7 kilograms since graduating from university. Our measurements showed him to have 27% body fat - which is average for the people we work with, but a quarter more than what is acceptable for men his age. He already had a noticeable paunch, something he had sworn in his youth that he would never have.

His blood pressure was 150 over 90, which is close to the borderline of hypertension. He admitted that the doctor advised him to change his diet and exercise more. His blood cholesterol level was 225 mg/dL, well above the ideal level. Roger has quit smoking for ten years, but admitted that he smokes an occasional cigarette when he's feeling particularly stressed. “I don’t consider it smoking and I don’t want to talk about it,” he told us.

Roger's eating habits explained both his excess weight and energy problems. More often than not, he would skip breakfast entirely (“I was always trying to lose weight”), but in the first half of the day he would “break down” by eating a muffin with a second cup of coffee. When he was in the office, he ate lunch at his desk, and although he tried his best to limit himself to a sandwich and salad, more often than not he could not resist a large scoop of ice cream. When he was on the road during the day, he most often bought a hamburger and fries or a few slices of pizza for lunch.

Around 4 p.m., feeling hungry, Roger tried to replenish his energy reserves by eating cookies, which were continuously supplied to his office. Throughout the day, his performance would rise and fall depending on how long he went without food and how many sweets he managed to eat. The biggest meal of the day was dinner, which he sat down to at 7:30–8 p.m. By this time he was already hungry as a wolf and ready to eat a large bowl of pasta or a substantial portion of chicken or meat and potatoes, as well as a bowl of well-dressed salad and a plate of bread. Only half the time was he able to resist the temptation to eat something else sweet before bed.

Roger almost always managed to avoid physical exercise, which could counteract overeating, neutralize negative emotions and restore mental abilities. His explanation was simple: he could not find the time and energy for this. Every morning at 6:30 he was already on the road. When he got home in the evening, the last thing he wanted to do after an hour and a half ride was jogging or working on an exercise bike. In his basement, other evidence of long-standing attempts to change something in this matter was gathering dust: a rowing machine, a treadmill and real deposits of dumbbells.

Driving with empty tanks

On an emotional level, Roger's main barriers were impatience and a negative attitude. When we explained this to him, he found our words very sobering. Because he grew up thinking of himself as an athlete, he always felt like everything would come easy to him.

In both college and university, Roger was considered a friendly and cheerful guy. In the first years of his work, he could make the whole office laugh. But over time, his humor reached its limit, instead of being friendly and gentle, it became sarcastic and harsh.

Clearly, a major factor in Roger's current vulnerability to negative emotions was his low energy. At the same time, in his life there was generally little reason for positive emotions. In his first seven years with the company, the workload was heavy, but the prospects were high. His boss helped him grow, supported his ideas, gave him freedom of action and helped him quickly move up the career ladder. The boss’s positive energy energized Roger as well.

Now the company was experiencing difficulties, expenses were being cut, layoffs began. Now everyone was expected to achieve greater results with less reward. His boss was given more authority, and Roger saw less of him and received less help from him. Roger began to feel that he was no longer a favorite. This had an impact not only on his mood, but also on his attitude towards work, and as a result, on his effectiveness: after all, energy is easily transferred, and a negative attitude can feed on itself. Leaders have a huge impact on the energy of their team. Roger's bad mood had a powerful effect on those who worked with him, just as his boss's perceived neglect had a powerful effect on Roger himself.

Relationships are one of the most powerful potential sources of emotional recovery. For many years, Roger considered Rachel his closest person and friend. Now that they have begun to spend much less time together, their romantic feelings are a thing of the past. Their relationship became “technical” - conversations now mainly concerned issues of supplying the house, finding out who would go pick up things from the dry cleaner, and who would take the children to the sports section. They barely talked about what was going on in their lives.

Struggle for concentration

The ways Roger used to manage his physical and emotional energy also helped him overcome his third barrier: lack of concentration. Fatigue, dissatisfaction with the boss, disagreements with Rachel, guilt towards the children and the growing demands of the new job - all this made it difficult to concentrate on work. Time management, which had not been a problem for him when he was a simple salesman, became a serious problem when he began managing forty employees in four states. For the first time since the start of his career, Roger found his attention was wandering and he was becoming less and less effective.

During a typical workday, Roger received between 50 and 75 emails and at least 25 voicemails. Since he spent at least half of his time on the road, he purchased a smartphone. This allowed him to work with email anytime, anywhere. But as a result, he began to constantly solve other people's issues instead of shaping his own agenda. Email also had a negative impact on his ability to concentrate on important tasks for long periods of time. He had previously considered himself creative and inventive (for example, he had once developed software to track customer relationships that the entire firm used), but now he had absolutely no time for long-term projects. Instead, he began to live “from mail to mail,” from request to request, from crisis to crisis. He rarely took breaks from work, and his attention became increasingly distracted during the workday.

Like many people around him, Roger rarely stopped working when he left the office doors. All the time of his long trips home was devoted to conversations on his cell phone. He answered emails in the evenings and on weekends. Even last summer, when he took his family to Europe for the first time, he still checked his email and voicemail every day. He felt like going back to work with a thousand emails and two hundred voicemails would be worse than spending an hour a day staying on top of things while on vacation. As a result, Roger was almost never able to completely disconnect from his work.

What really matters?

So Roger now spent so much of his life responding to outside demands that he had almost lost track of what he really wanted out of life. When we asked him what gives him the greatest feeling of fullness and richness in life, he could not answer us. He admitted that he did not feel particularly enthusiastic at work, although his authority and status had increased. He also had no strong feelings about his home, although it was clear that he loved his wife and children and put them first in his life. A powerful source of energy, which is based on a clear understanding of purpose and purpose, was simply not available to Roger. Disconnected from deeper values, he had no motivation to take better care of his physical condition, control his impatience, manage his time, or focus his attention. Busy solving an endless stream of problems, he could not find the energy or time to comprehend the causes and consequences of his decisions. Any reflection about his life only brought him irritation, because it seemed to him that he could not change anything.

Roger had almost everything he dreamed of, but he only felt tired, disappointed, driven and underappreciated. In addition, in his words, Roger felt like a victim of factors that were beyond his control.

3. High efficiency pulsation

Balance between stress and recovery

The idea of maximizing performance by alternating periods of activity and rest was first proposed by Flavius Philostratus (170–245), who wrote a training manual for Greek athletes. Soviet sports scientists resurrected the idea in the 1960s and used it to train Olympians with great success. Nowadays, work-rest ratio is at the very center of the training methods of elite athletes around the world.

The scientific basis of this approach has become more precise and subtle over the years, but its principles have not changed in the two thousand years since the idea was first introduced. Following a period of activity, our body must replenish basic biochemical energy sources. This process is called "compensation". Increase the intensity of your workout or work during a competition and you will have to proportionally increase the amount of energy you need to restore. If this is not done, the athlete’s results will noticeably decrease.

Energy is simply the ability to do work. Our most fundamental biological need is to expend and store energy.

We expend energy to do work, but restoring energy is much more than just not doing work. Almost all the elite athletes we have worked with have an imbalance between energy expenditure and energy storage. They were either overtrained or undertrained in one or more areas: physically, emotionally, mentally or spiritually. Both undertraining and overtraining have consequences in the form of decreased performance, which can manifest as injury and illness, anxiety, negative attitudes and anger, difficulty concentrating, and loss of enthusiasm. And the real breakthroughs happened when we were able to help them learn to manage energy more skillfully. In these cases, they not only systematically increased the energy reserves they were lacking, but also built regular recovery procedures into their training and competition schedules.

The balance between stress and recovery is important not only for athletic performance, but also for managing energy in all facets of our lives. When we waste energy, we empty our gas tank. When we restore energy, we fill it up again. Expending too much energy without sufficient replenishment leads to exhaustion. Excess energy without sufficient use leads to atrophy and weakness. Remember what happens to an arm placed in a cast: after a very short time, its muscles begin to atrophy from lack of use. The results that we achieve over many years of fitness are seriously reduced after just one week of inactivity, and after just four weeks they disappear completely.

The same processes occur in the emotional, mental and spiritual spheres. Emotional depth and vitality depend on active interaction with other people and on our own feelings. Mental acuity decreases in the absence of constant intellectual work. Spiritual energy depends on regularly returning to our deepest values and taking responsibility for our behavior. Operating at full capacity requires cultivating a dynamic balance between energy expenditure (stress) and energy recovery (rest) in all directions.

Pulse of life

Nature itself is filled with pulse, rhythm, wave movement, alternation of activity and rest. Think about the ebb and flow of the tides, the changing seasons, the daily sunrises and sunsets. All living things also follow the rhythms of life: birds migrate, bears hibernate, squirrels collect nuts, fish spawn - and all this happens at predictable intervals.

Human life is also subject to rhythms – both natural and those inherent in genes. Seasonal health disorders (for example, winter depression) are caused by both changes in seasonal rhythms and the body's inability to adapt. Our breathing, brain waves, hormone levels, blood pressure - they all change rhythmically and are the basis of both our health and ill health.

We are vibrational organisms in a vibrational universe. Rhythm is the basis of our life. Oscillatory processes manifest themselves at the most fundamental levels of our existence. A healthy balance of activity and rest underpins our ability to develop full power, achieve peak performance and maintain health. On the contrary, linearity is guaranteed to lead to illness and death. Remember what an encephalogram or cardiogram of a healthy person looks like, and compare it with its opposite - a straight line.

At a higher level, the structure of our activity and rest is associated with daily biorhythms. In the early 1950s, it was discovered that our sleep is broken down into chunks of 90 to 120 minutes. The REM phase, during which brain activity is quite high and we dream, is followed by deep sleep, when the brain calms down and deep recovery occurs. In the 1970s, further research showed that rhythms of approximately the same periodicity operate during wakefulness (they were called “ultradian”, that is, occurring several times a day).

These ultradian rhythms help explain the ebb and flow of our energy throughout the day. Physiological indicators - heart rate, hormone levels, muscle tension and brain waves - increase during the first half of the cycle, creating a state of alertness. After about an hour, these numbers begin to decrease. Somewhere between 90 and 120 minutes our body begins to crave rest and recovery. Signs of this include yawning, stretching, bouts of hunger, growing tension, difficulty concentrating, the desire to put off work and get distracted, and a high percentage of errors. We can overcome these natural cycles only by mobilizing all our strength and producing stress hormones, which are designed to regulate our actions in dangerous situations.

Time between serves

To live like a sprinter, we need to break life into a series of intervals that correspond to our physiological capabilities and the rhythm of their change. This idea first took shape in the mind of one of us, Jim, when he was working with world-class tennis players. Dealing with the psychology of achieving top results, he wanted to highlight those factors that separate champions from the rest of the “peleton.” Jim spent hundreds of hours watching champions play and watching tapes of their matches. To his growing surprise, he was unable to notice any significant difference in the way they behaved during the game. It was only when he noticed what they were doing between points that he saw the difference. All the best players behaved almost identically between innings without realizing it. This included how they walked to the service line, how they held their head and shoulders, what their eyes were focused on, how they breathed, and even how they talked to themselves.

It became clear to Jim that they instinctively used the time between points to maximize recovery. Now he began to notice that low-level players did not have such rest procedures at all. When he managed to put heart rate monitors on the champions (which was much more difficult in the 1970s than it is now), he came to another surprising discovery. 16–20 seconds after the end of the point, the pulse of the best players decreased by 20 beats per minute. By developing effective energy recovery routines, these players have found a way to recover huge amounts of energy within seconds. Their less successful opponents maintained a high heart rate throughout the match, regardless of their fitness level.

Having such precise “rituals” of behavior between points has proven to be a key factor in achieving superior results. Imagine two players of approximately equal skill level and approximately equal level of physical fitness. The match is in its third hour. One of them is regularly restored between draws, while the other is not. Obviously, the second player will be much more tired. But fatigue, in turn, also has a kind of cascading effect: a tired person is more susceptible to negative emotions such as anger and irritation, which are likely to further increase his pulse and cause his muscles to tense when there is no load, preventing them from relaxing. Physical fatigue makes it difficult to concentrate. All this applies not only to sports, but also to any work, including sedentary work. Imagine sitting at your desk for long hours, solving complex problems. Fatigue is guaranteed, as well as negative emotions and distraction, which will inevitably lead to decreased productivity.

When applied to tennis, Jim proved this with precise measurements. The more constant a player's heart rate was, the worse the quality of his play became over the course of the match and the worse the final result. Too much energy expenditure without sufficient recovery led to a chronic increase in heart rate. In the same way, a constantly low heart rate also affected the result - this is a sure sign that the player is not giving his all or has admitted defeat in advance.

Even in sports such as golf (which require little physical energy), rituals are important to maintain a balance between energy expenditure and energy recovery. Jack Nicklaus was known not only for his technical skills and grit, but also for his ability to analyze the ingredients of his success:

Recovery while working

Restoring the organization's energy

Maintaining a balance between stress and recovery can be very important at the organizational level as well. Bruce F. runs a department for a large telecommunications company, and he took our program with members of his leadership team. We found out that he likes to hold meetings that last three to four hours without a break. Possessing endless reserves of energy, Bruce acknowledged that there was an element of machismo in such marathons, but believed that the ability to concentrate for long periods of time was the main characteristic of a good leader. We pointed out to him that if his goal was to achieve maximum productivity, then his way of managing the energy of the team was incorrect. To withstand such demands, his employees, of course, made every effort - with more or less success. But none of them could be as concentrated at the end of the meeting as at the beginning.

At first, Bruce was quite skeptical about our ideas about the need to restore energy. But Jim's research on how tennis players recover energy between serves and what results this leads to changed his mind. At the end of our course, Bruce said that he was going to personally experiment with short periods of rest during the workday. A few days later he told us that after such breaks he felt better not only physically, but also emotionally. An enthusiast by nature, Bruce continued to experiment with different forms of intermittent recuperation and eventually found two methods that allowed him to completely take his mind off his work and achieve the greatest recovery.

The first method involved walking up and down a dozen floors of stairs in his office building. And the second way turned out to be juggling. After he left us, he began to learn how to juggle three balls. After a few months he reached six, and this activity completely took his mind off work and gave him a pure feeling of joy. A few weeks after his visit, Bruce completely changed the way he conducted meetings. He began scheduling a strictly mandatory fifteen-minute break every ninety minutes and demanded that no one discuss business during those breaks. “People took my hint. These breaks literally freed up our organization. Now we can do more in less time, and with more pleasure!”

4. Physical energy

Firewood for the fire

The importance of physical energy seems obvious to athletes and people involved in strenuous physical labor. Since everyone else is judged primarily on the results of intellectual work, we tend to underestimate the extent to which physical energy influences their results. Often the influence of physical fitness on labor productivity is equal to zero. In fact, physical energy is the fundamental source of movement—even for the most sedentary activities. Not only is it the foundation of vitality, but it also influences our ability to manage emotions, maintain focus, create, and simply stay on track. Leaders and managers make a serious mistake in thinking that they can ignore the physical side of human energy and expect maximum productivity from their subordinates.

When we first met Roger B., we found that he had never thought about energy management in any aspect of his life and did not pay attention to his physical condition. He, of course, understood that he would feel better if he went to bed earlier and exercised regularly, but he did not have enough time for the minimum. He knew his diet wasn't healthy, but he didn't have the will to change anything. Instead, he simply tried not to think about the consequences of his habits.

At the lowest level, physical energy arises from the interaction of oxygen and glucose. That is, from a practical point of view, the size of our energy reserves depends on our breathing, on what and when we eat, on the quantity and quality of our sleep, on the degree of periodic recovery during the working day and on the general level of fitness and endurance of the body. Creating a rhythmic balance between the expenditure and storage of physical energy ensures that the level of our energy reserves remains at a roughly constant level. Putting in extra effort and stepping outside our comfort zone—with subsequent recovery, of course—allows us to build up our reserves.

The most important rhythmic processes in our lives are the obvious ones - breathing and eating. None of us thinks much about breathing. Oxygen shows its value only in those rare situations when we do not have enough of it - when, for example, we choke on food or choke on water in the sea. Even the most significant changes in our breathing go unnoticed. Anxiety and anger, for example, lead to more rapid and shallow breathing, which is in preparation for an immediate response to immediate danger. However, this type of breathing very quickly reduces the amount of energy available to us and reduces the ability to restore mental and emotional balance. By the way, this is precisely what explains the mechanism of the simplest remedy against anxiety and anger - deep breathing.

Breathing is a powerful means of self-regulation - both for storing energy and for deep rest. Lengthening the exhalation, for example, leads to the appearance of a wave of relaxation. Inhaling for three counts and exhaling for six counts reduces agitation and calms the body, brain and emotions. Deep, smooth and rhythmic breathing is a source of energy and concentration, as well as relaxation and calm. This rhythm is the real basis of health.

Strategic nutrition

The second most important source of physical energy is food. The cost of malnutrition is known - it is a lack of glycogen, which is the fuel for generating physical energy. Most of us are unfamiliar with long-term malnutrition, but have experienced short-term hunger and know the impact it has on productivity. On an empty stomach it is very difficult to concentrate on anything other than thoughts about food. On the other hand, chronic overeating gives us excess fuel, which only leads to obesity and health problems, without any productivity gains. Consuming large amounts of fats, sugars and simple carbohydrates allows you to store energy, but in much less efficient and capacious forms than consuming low-fat proteins and complex carbohydrates found in vegetables and grains.

Proper nutrition, among other benefits - weight loss, healthier appearance and improved health - contributes to the accumulation of positive energy. When you wake up in the morning, 8-12 hours after your last meal, your blood glucose levels are at their lowest, although you don't yet feel hungry. Breakfast is the most important meal because it not only raises your blood glucose levels, but also starts all the metabolic processes you will need throughout the day.

It is important to consume foods with a low glycemic index, which determines the rate at which sugar from food enters the bloodstream (see Appendix 1). Slow release of sugar into the blood provides a more uniform supply of energy. Breakfast foods that provide long-lasting energy include whole grains, proteins, and low-glycemic fruits such as strawberries, pears, grapefruits, and apples. Conversely, high-glycemic foods, such as baked goods or sugary cereals, provide very high energy, but for a short time - after half an hour their effect ends. Even the traditionally considered healthy breakfast of orange juice and butter-free baked goods has a high glycemic index and is therefore a poor source of energy.

The number of meals we eat throughout the day also affects our ability to function at full capacity and maintain high productivity. Five or six meals of low-calorie, but nutritious food provide a constant flow of energy. Even the most energy-rich foods cannot provide energy during the four to eight hours between meals. In one study, subjects were placed in a room in which there was no clock or other clues about the passage of time. They were given unhindered access to food and were asked to eat as soon as they felt hungry. It turned out that the average break between meals was sixty-nine minutes.

Consistent productivity doesn't just depend on eating at regular intervals. It is important to eat just enough each time to maintain your energy levels until your next meal. Controlling your portion sizes is important not only for managing your weight, but also for regulating your energy. Problems will be caused by both excessive and too frequent nutrition and insufficient and infrequent nutrition. Snacking between main meals is acceptable, but within the range of 100–150 kilocalories and, again, taking into account the glycemic index of foods, which should remain low.

Circadian biorhythms and sleep

The next important source of recuperation is sleep. Most of the people we spoke to had sleep disorders. And very few of them clearly understood how much sleep deprivation affected their efficiency and power levels - both at work and at home.

Even a little sleep deprivation—in our terms, lack of recovery—has a significant impact on strength, heart function, mood, and overall energy levels. There are plenty of studies on how mental productivity—reaction time, concentration, memory, logical and analytical abilities—falls rapidly as sleep debt accumulates. Sleep needs change with age and may have gender and genetic variations, but scientists agree on one thing: the average person needs 7-8 hours of sleep a night for their body to function optimally. Several studies have shown that when a person is isolated from daylight, they sleep about 7-8 hours out of 24.

The largest study, conducted by psychologist Dann Kripke and his colleagues, studied the sleep of one million people over 6 years. Premature mortality from any cause was lowest among people who slept 7 to 8 hours a night. For those who slept less than 4 hours, premature mortality was 2.5 times higher compared to the first group, and for those who slept more than 10 hours, it was 1.5 times higher. Both too little and too much recovery were found to increase the risk of premature death.

The time of day we sleep also affects our energy levels, health and productivity. Numerous studies have shown that almost twice as many accidents occur on the night shift than on the day shift. Those who work at night also have an increased risk of coronary artery disease and heart attack. It has been observed that many disasters - Chernobyl, Bhopal, the Exxon Valdez tanker, Three Mile Island - occurred in the middle of the night. People who made disastrous decisions worked long hours and did not get enough sleep. The Challenger shuttle disaster in 1986 occurred when NASA officials decided to continue launch operations after personnel had worked twelve hours without a break.

The longer, more continuously, and later you work at night, the more mistakes you make and the less effective you are at work.

The pulse of our day

You don't have to work a night shift for fatigue and lack of recovery to have an impact on your energy levels and efficiency. Just as we go through different levels of sleep at night, we go through different levels of energy and power during the day. They are tied to the ultradian rhythms of wakefulness. Unfortunately, most of us try to overcome and ignore these natural rhythms. The demands on us are so intense and so absorbing that they completely distract our attention from the very subtle internal signals of our body that require restoration.

In the absence of artificial interventions, our energy reserves naturally ebb and flow throughout the day. Between 3 and 4 p.m. we reach the lowest phase of both circadian and ultradian rhythms. It is at this moment that we feel the most tired. The likelihood of incidents and accidents at this time is highest. This, perhaps, can explain the fact that in the cultures of many nations there were customs of afternoon rest, which are disappearing in our “24/7” world.

NASA introduced a special program to combat personnel fatigue when it discovered that after a short nap of forty minutes, productivity increased by 34% and alertness doubled. A Harvard University study showed that people whose work productivity dropped by 50% during the day were able to work at 100% productivity if they were allowed one hour of sleep in the afternoon.

Winston Churchill came to this conclusion himself:

Raising the bar

Considering the benefits that even the simplest exercise brings, it seems incredible how many of us do not do it at all. The explanation for this is surprisingly simple: developing strength and endurance requires going beyond our comfort zone. It takes some time for the benefits of exercise to become noticeable, and most of us stop exercising, sometimes several days before this point occurs.

Training our muscular strength and cardiovascular system has positive effects on our health, our energy levels and our performance (see data below). Since Kenneth Cooper's book Aerobics appeared in the mid-1960s, it has been common wisdom that the best way to achieve endurance is through sustained, steady aerobic exercise. Our experience suggests that interval training gives the best results. This type of training originated in Europe in the 1930s as a way to increase the speed and endurance of runners. It is based on short periods of intense activity alternating with short periods of rest. In this mode, you can do more, more intense work.

The link between exercise and performance

– DuPont reported a 47.5% reduction in absenteeism over a six-year period among participants in a corporate fitness program. In addition, program participants reduced the number of sick days by 14% compared to those who did not participate in the program.

– A study published in the journal Ergonomics reported that “mental productivity is significantly higher in people who exercise. They made 27% fewer errors on tasks requiring concentration and short-term memory compared to those who did not exercise.”

5. Emotional energy

Turning a threat into a challenge

Physical energy is merely the fuel intended to ignite our emotional talents and skills. To perform at our highest level of productivity, we must experience positive emotions based on joy, challenge, adventure and opportunity. Emotions based on threat or lack of something - fear, disappointment, anger, sadness - have only a destructive effect on our effectiveness and are associated with the production of stress hormones, especially cortisol. We could define “emotional intelligence” as the ability to manage one's emotions in order to achieve high levels of positive energy and develop to one's full potential. Simply put, the key muscles for achieving a positive emotional state are self-confidence, self-control, communication skills and empathy. The small, supportive muscles are patience, openness, trust and pleasure.

The ability to use emotional muscles to improve performance depends on the balance between their regular use and subsequent recovery. Just as we deplete our heart muscle or biceps by subjecting them to constant stress, we also destroy our emotional state if we constantly waste emotional energy without restoring it. If our emotional muscles are too weak to cope with a situation - for example, if we are insecure or impatient - we must systematically expand their capacity by developing rituals that take us beyond our current capabilities, followed by mandatory recovery.

Emotional and physical energy reserves are inextricably linked. When physical energy reserves begin to deplete, we experience a feeling of anxiety. We are moving into the high negative energy quadrant. This is exactly what happened in the life of Roger B. Because he paid very little attention to the renewal of physical energy, the capacity of his physical “accumulators” began to decrease over time. At the same time, he understood that the demands on him were constantly growing. Feeling less attention from his boss, worried about work, and disconnected from his family, Roger became increasingly irritable, anxious, and defensive.

As fuel, negative emotions are very costly and ineffective: like a gluttonous engine, they empty our reserves very quickly. Negative emotions are doubly contraindicated for leaders and managers because of their contagiousness. If we instill fear, anger, and defensiveness in our employees, we undermine their ability to be productive. It is well known that chronic negative emotions—especially anger and depression—are associated with a wide range of disorders and diseases.

Our client Roger B. had not yet reached the stage of serious health problems, although he had already begun to complain of frequent headaches and back pain that distracted him from work. When he began working with us, he noticed other manifestations of the influence of negative energy on his life. On days when he felt anxious, his concentration and willpower decreased. As impatience grew, his relationships with his colleagues became strained, and the team produced less results.

Pleasure and Renewal

Simply switching channels is an effective method of emotional recharging. Over the decades of our work, we have been constantly surprised and horrified by how rarely most people do something that simply brings joy and fuels emotions. We always ask our clients: how often do they experience joy in their lives? The most common answer is “rarely.” Take a closer look at your own life. How many hours a week do you devote to something that brings you only pleasure? What percentage of your time do you spend in a state that you might describe as deep relaxation? When was the last time you felt like you were able to completely forget about your daily problems?

Any activity that excites you or gives you self-confidence brings joy. This could be singing, gardening, dancing, yoga, reading books, playing sports, visiting museums, concerts and exhibitions, even spending time alone after a busy working day. We have found that the key is to give this time the highest priority, the "holy of holies" status. And the point here is not only that pleasure itself is a reward, but that it is a critical ingredient in maintaining long-term performance.

The depth and quality of emotional release are important to us. They depend on how absorbed, enriched and enlivening you are by your chosen activity. For example, for most people the easiest way to relax and unwind is television. But, unfortunately, this is a kind of intellectual fast food. Television can provide temporary relief, but it is very rarely "nutritious" and it is very easy to overeat. Researchers such as Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi have found that prolonged television viewing actually leads to irritability and depression. And vice versa - the richer and deeper the source of emotional restoration, the more opportunities we have to replenish our reserves and the more resilient we become.

Unity of opposites

The most obvious sign of emotional capacity is the ability to experience a wide range of feelings. Because our brains have difficulty processing conflicting impulses, we tend to take certain positions and value some emotional skills while neglecting and sometimes even rejecting others. We may, for example, overestimate toughness of character and underestimate tenderness, or vice versa, although both of these qualities are equally important. The same applies to other opposites: self-control and spontaneity, directness and delicacy, stinginess and generosity, openness and caution, patience and haste, confidence and modesty.

Try to imagine how wide the range of your personal emotional “muscles” is. You will likely find that you are significantly stronger on one end of the spectrum than the other. Pay attention to your assessment of the relative advantages of opposing qualities. In our opinion, the best way to achieve depth and richness of emotions is to equally value feelings that seem opposite to you, and not take sides with one of them. Achieving full emotional power requires what the Stoic philosophers called the “reciprocity of virtues.” They believed that none of the virtues could exist on their own. Directness without delicacy, for example, can result in callousness.

We are the sum of our complexes and contradictions. While developing our emotional power, we must concentrate our efforts on developing those feelings that we lack. The ultimate goal is the ability to easily and flexibly move from one feeling to the opposite.

Remember

– To perform at our highest levels of performance, we must experience positive emotions: joy, challenge, adventure and opportunity.

– The key “muscles” for creating positive emotional energy are self-confidence, self-control, communication skills and empathy.

– Negative emotions are needed for survival, but from the point of view of high efficiency they are too costly and energetically unprofitable.

– The ability to accumulate positive emotions under conditions of intense stress is the basis of effective leadership.

– The development of emotional “muscles” that support high productivity depends on the balance between their regular tension and relaxation.

Life at full capacity. Energy management is the key to high performance, health and happiness

Preface

Cure for downshiftingMany have been waiting for this book for a long time. They waited, not yet suspecting its existence, title or authors. They waited, leaving the office with a greenish face, drinking liters of coffee in the morning, not finding the strength to take on the next priority task, struggling with depression and despondency.

And finally they waited. There were specialists who gave a convincing, detailed and practical answer to the question of how to manage the level of personal energy. Moreover, in various aspects - physical, intellectual, spiritual... What is especially valuable are practitioners who have trained leading American athletes, FBI special forces and top managers of Fortune 500 companies.

Admit it, reader, when you came across another article about downshifting, the thought probably crossed your mind: “Maybe I should give up everything and go somewhere to Goa or a hut in the Siberian taiga?..” The desire to give up everything and send everyone to any of the short and succinct Russian words is a sure sign of lack of energy.

The problem of energy management is one of the key ones in self-management. One of the participants in the Russian Time Management community once came up with the formula “T1ME” management - from the words “time, information, money, energy”: “time, information, money, energy.” Each of these four resources is critical to personal effectiveness, success and development. And if there is quite a lot of literature on time, money and information management, then in the field of energy management there was a clear gap. Which is finally starting to fill up.

In many ways, of course, you can argue with the authors. Undoubtedly, they, like many Western specialists, tend to absolutize their approach and strictly oppose it to the “old paradigms” (for which it is in fact not a negation at all, but an organic continuation and development). But this in no way detracts from the main advantages of the book - relevance, simplicity, technology.

Read, get everything done and fill your Time with Energy!

Gleb Arkhangelsky, General Director of the Time Organization company, creator of the Russian Time Management community www.improvement.ru

Part one Full power driving forces

1. At full power

The most precious resource is energy, not time

We live in a digital age. We are running at full speed, our rhythms are accelerating, our days are cut into bytes and bits. We prefer breadth to depth and quick response to thoughtful decisions. We glide across the surface, ending up in dozens of places for a few minutes, but never staying anywhere for long. We fly through life without pausing to think about who we really want to become. We are connected, but we are disconnected.Most of us are just trying to do the best we can. When demands exceed our capabilities, we make decisions that help us break through the web of problems but eat up our time. We sleep little, eat on the go, fuel ourselves with caffeine and calm ourselves down with alcohol and sleeping pills. Faced with unrelenting demands at work, we become irritable and our attention is easily distracted. After a long day of work, we return home completely exhausted and perceive family not as a source of joy and restoration, but as just another problem.

We have surrounded ourselves with diaries and task lists, handhelds and smartphones, instant messaging systems and “reminders” on computers. We believe this should help us manage our time better. We pride ourselves on our ability to multitask, and we demonstrate our willingness to work from dawn to dusk everywhere, like a medal for bravery. The term “24/7” describes a world where work never ends. We use the words “obsession” and “madness” not to describe madness, but to talk about the past working day. Feeling that there will never be enough time, we try to pack as many things as possible into each day. But even the most effective time management does not guarantee that we will have enough energy to get everything done.

Are you familiar with such situations?

– You are in an important four-hour meeting where not a second is wasted. But the last two hours you spend the rest of your energy only on fruitless attempts to concentrate;

– You carefully planned all 12 hours of the upcoming working day, but by the middle of it you completely lost energy and became impatient and irritable;

– You are going to spend the evening with the children, but are so distracted by thoughts about work that you cannot understand what they want from you;

– You, of course, remember about your wedding anniversary (the computer reminded you of this this afternoon), but you forgot to buy a bouquet, and you no longer have the strength to leave the house to celebrate.

Energy, not time, is the main currency of high efficiency. This idea revolutionized our understanding of what drives high performance over time. She led our clients to reconsider the principles of managing their own lives - both personal and professional. Everything we do, from walking with our children to communicating with colleagues and making important decisions, requires energy. This seems obvious, but it is what we most often forget. Without the right quantity, quality and focus of energy, we endanger any task we undertake.

Each of our thoughts or emotions has energetic consequences - for worse or for better. The final assessment of our lives is not based on the amount of time we spend on this planet, but on the basis of the energy we invest in that time. The main idea of this book is quite simple: effectiveness, health and happiness are based on skillful energy management.

Of course, there are bad bosses, toxic work environments, difficult relationships, and life crises. However, we can control our energy much more completely and deeply than we imagine. The number of hours in a day is constant, but the quantity and quality of energy available to us depends on us. And this is our most valuable resource. The more responsibility we take for the energy we bring into the world, the stronger and more effective we become. And the more we blame other people and circumstances, the more our energy becomes negative and destructive.

If you could wake up tomorrow with more positive and focused energy that you could invest in your work and family, would that improve your life? If you are a leader or manager, would your positive energy change the work environment around you? If your employees could rely on more of your energy, would the relationships between them change and would this have an impact on the quality of your own services?

Leaders are the conductors of organizational energy—in their companies and families. They inspire or demoralize those around them—first by how effectively they manage their own energy, and then by how they mobilize, focus, invest, and renew the collective energy of their employees. Skillful management of energy, individual and collective, makes possible what we call the achievement of full power.

To be fully energized, we must be physically energized, emotionally engaged, mentally focused, and united in spirit to achieve goals that lie beyond our selfish interests. Working at full capacity begins with a desire to start work earlier in the morning, an equal desire to return home in the evening, and drawing a clear line between work and home. It means the ability to immerse yourself in your mission, whether it's solving a creative problem, leading a group of employees, spending time with the people you love, or having fun. Working at full capacity requires a fundamental lifestyle change.

According to results published in 2001 by Gallup survey, only 25% of employees in American companies work at full capacity. About 55% work at half capacity. The remaining 20% are “actively opposed” to work, meaning they are not only unhappy in their professional lives, but also constantly share this feeling with their colleagues. The cost of their presence at work is estimated at trillions of dollars. What's even worse is that the longer people work in an organization, the less energy they devote to it. After the first six months of work, only 38% are working at full capacity, according to Gallup. After three years, this figure drops to 22%. Look at your life from this point of view. How fully are you involved in your work? What about your colleagues?

Current page: 1 (book has 11 pages total) [available reading passage: 3 pages]

Jim Lauer, Tony Schwartz

Life at full capacity. Energy management is the key to high performance, health and happiness

Preface

Cure for downshifting

Many have been waiting for this book for a long time. They waited, not yet suspecting its existence, title or authors. They waited, leaving the office with a greenish face, drinking liters of coffee in the morning, not finding the strength to take on the next priority task, struggling with depression and despondency.

And finally they waited. There were specialists who gave a convincing, detailed and practical answer to the question of how to manage the level of personal energy. Moreover, in various aspects - physical, intellectual, spiritual... What is especially valuable are practitioners who have trained leading American athletes, FBI special forces and top managers of Fortune 500 companies.

Admit it, reader, when you came across another article about downshifting, the thought probably crossed your mind: “Maybe I should give up everything and go somewhere to Goa or a hut in the Siberian taiga?..” The desire to give up everything and send everyone to any of the short and succinct Russian words is a sure sign of lack of energy.

The problem of energy management is one of the key ones in self-management. One of the participants in the Russian Time Management community once came up with the formula “T1ME” management - from the words “time, information, money, energy”: “time, information, money, energy.” Each of these four resources is critical to personal effectiveness, success and development. And if there is quite a lot of literature on time, money and information management, then in the field of energy management there was a clear gap. Which is finally starting to fill up.

In many ways, of course, you can argue with the authors. Undoubtedly, they, like many Western specialists, tend to absolutize their approach and strictly oppose it to the “old paradigms” (for which it is in fact not a negation at all, but an organic continuation and development). But this in no way detracts from the main advantages of the book - relevance, simplicity, technology.

Read, get everything done and fill your Time with Energy!

Gleb Arkhangelsky, General Director of the Time Organization company, creator of the Russian Time Management community www.improvement.ru

Part one

Full Power Driving Forces

1. At full power

The most precious resource is energy, not timeWe live in a digital age. We are running at full speed, our rhythms are accelerating, our days are cut into bytes and bits. We prefer breadth to depth and quick response to thoughtful decisions. We glide across the surface, ending up in dozens of places for a few minutes, but never staying anywhere for long. We fly through life without pausing to think about who we really want to become. We are connected, but we are disconnected.

Most of us are just trying to do the best we can. When demands exceed our capabilities, we make decisions that help us break through the web of problems but eat up our time. We sleep little, eat on the go, fuel ourselves with caffeine and calm ourselves down with alcohol and sleeping pills. Faced with unrelenting demands at work, we become irritable and our attention is easily distracted. After a long day of work, we return home completely exhausted and perceive family not as a source of joy and restoration, but as just another problem.

We have surrounded ourselves with diaries and task lists, handhelds and smartphones, instant messaging systems and “reminders” on computers. We believe this should help us manage our time better. We pride ourselves on our ability to multitask, and we demonstrate our willingness to work from dawn to dusk everywhere, like a medal for bravery. The term “24/7” describes a world where work never ends. We use the words “obsession” and “madness” not to describe madness, but to talk about the past working day. Feeling that there will never be enough time, we try to pack as many things as possible into each day. But even the most effective time management does not guarantee that we will have enough energy to get everything done.

Are you familiar with such situations?

– You are in an important four-hour meeting where not a second is wasted. But the last two hours you spend the rest of your energy only on fruitless attempts to concentrate;

– You carefully planned all 12 hours of the upcoming working day, but by the middle of it you completely lost energy and became impatient and irritable;

– You are going to spend the evening with the children, but are so distracted by thoughts about work that you cannot understand what they want from you;

– You, of course, remember about your wedding anniversary (the computer reminded you of this this afternoon), but you forgot to buy a bouquet, and you no longer have the strength to leave the house to celebrate.

Energy, not time, is the main currency of high efficiency. This idea revolutionized our understanding of what drives high performance over time. She led our clients to reconsider the principles of managing their own lives - both personal and professional. Everything we do, from walking with our children to communicating with colleagues and making important decisions, requires energy. This seems obvious, but it is what we most often forget. Without the right quantity, quality and focus of energy, we endanger any task we undertake.

Each of our thoughts or emotions has energetic consequences - for worse or for better. The final assessment of our lives is not based on the amount of time we spend on this planet, but on the basis of the energy we invest in that time. The main idea of this book is quite simple: effectiveness, health and happiness are based on skillful energy management.

Of course, there are bad bosses, toxic work environments, difficult relationships, and life crises. However, we can control our energy much more completely and deeply than we imagine. The number of hours in a day is constant, but the quantity and quality of energy available to us depends on us. And this is our most valuable resource. The more responsibility we take for the energy we bring into the world, the stronger and more effective we become. And the more we blame other people and circumstances, the more our energy becomes negative and destructive.

If you could wake up tomorrow with more positive and focused energy that you could invest in your work and family, would that improve your life? If you are a leader or manager, would your positive energy change the work environment around you? If your employees could rely on more of your energy, would the relationships between them change and would this have an impact on the quality of your own services?

Leaders are the conductors of organizational energy—in their companies and families. They inspire or demoralize those around them—first by how effectively they manage their own energy, and then by how they mobilize, focus, invest, and renew the collective energy of their employees. Skillful management of energy, individual and collective, makes possible what we call the achievement of full power.

To be fully energized, we must be physically energized, emotionally engaged, mentally focused, and united in spirit to achieve goals that lie beyond our selfish interests. Working at full capacity begins with a desire to start work earlier in the morning, an equal desire to return home in the evening, and drawing a clear line between work and home. It means the ability to immerse yourself in your mission, whether it's solving a creative problem, leading a group of employees, spending time with the people you love, or having fun. Working at full capacity requires a fundamental lifestyle change.

According to results published in 2001 by Gallup 1

American Institute of Public Opinion, founded in 1935. Here and further, where not otherwise noted, notes are given by the editor.

Survey, only 25% of employees in US companies are working at full capacity. About 55% work at half capacity. The remaining 20% are “actively opposed” to work, meaning they are not only unhappy in their professional lives, but also constantly share this feeling with their colleagues. The cost of their presence at work is estimated at trillions of dollars. What's even worse is that the longer people work in an organization, the less energy they devote to it. After the first six months of work, only 38% are working at full capacity, according to Gallup. After three years, this figure drops to 22%. Look at your life from this point of view. How fully are you involved in your work? What about your colleagues?

Living laboratoryThe idea of the importance of energy first came to us in the “living laboratory” of professional sports. For thirty years, our organization has worked with world-class athletes to determine what allows some of them to perform at their best over the long term under constant competitive pressure. Our first clients were tennis players - more than eighty of the world's best players such as Pete Sampras, Jim Courier, Arancha Sanchez-Vicario, Sergi Brugueira, Gabriela Sabatini and Monica Seles.

They usually came to us at the moments of the most intense struggle, and our intervention often led to the most serious results. After our work, Arancha Sanchez-Vicario won the U.S. for the first time. Open 2

The US Open, one of the four Grand Slam tournaments.

And she became first in the world rankings - both in singles and doubles. Sabatini won her only U.S. Open. Brugueira rose from world No. 79 to the top ten and won the French Open twice. 3

The French Open, one of the four Grand Slam tournaments.

Then athletes from other sports began to come to us - golfers Mark O'Mira and Ernie Els, hockey players Eric Lindros and Mike Richter, boxer Ray "Boom Boom" Mancini, basketball players Nick Anderson and Grant Hill, speed skater Dan Jensen, who won the only his life's Olympic gold medal only after two years of intensive training with us.

What made our method unique was that we did not spend a second studying the technical or tactical skills of our players. The common cliché is that if you find a talented person and teach him the right skills, he will produce the best results. But in practice this happens very rarely. It turns out that energy is the unobvious factor that allows you to “ignite” talent to its full potential. We never wondered how Seles hits the ball on a serve, how Lindros flicks the puck, or how Hill shoots free throws. They were all extremely gifted before they came to us. Instead, we focused on helping them learn to manage their own energy to accomplish whatever task they were faced with.

Athletes have proven to be very demanding experimental subjects. They were not at all satisfied with “uplifting” conversations or sophisticated theories. They were interested in measurable and lasting results - the number of aces 4

In tennis terminology, a point won by one hit. ** The ball hits the opposing team's scoring zone.

From the first serve, percentage of free throws, victories in tournaments. They wanted to be sure they could make the eighteenth hole, make a last-second three-pointer, or score a touchdown in the Super Bowl. Everything else is chatter. If we could not help athletes achieve the results they need, our work in this area would not be measured in decades. We have learned to be responsible for the numbers.

As word of our success in sports began to spread, we began to receive numerous offers to “export” our model to other areas of human activity that require high impact. We worked with FBI hostage teams, marshals, and emergency medical technicians. Nowadays, the bulk of our work is related to business - with CEOs and entrepreneurs, managers and salespeople, and more recently, also with teachers and officials, lawyers and medical students. Our corporate clients include Fortune 500 companies such as PepsiCo, Estee Lauder, Pfizer, Brisol-Myers Squibb, Hyatt Corporation and many others.

As we worked in these new fields, we discovered something completely unexpected: the demands placed on ordinary people doing ordinary jobs far exceeded the demands placed on any professional athlete we had ever worked with. How is this possible?

If you take a closer look, this is not surprising. Professional athletes typically spend 90% of their time training so they can compete the remaining 10% of the time. Their whole life is organized around receiving, retaining and renewing the energy needed for a short period of competition. They build very precise procedures for managing their energy in all areas of life - eating and sleeping, studying and resting, charging and discharging emotions, concentrating and psychologically preparing for the tasks they set for themselves. Ordinary people, not accustomed to spending time on such detailed preparation, must work to the maximum of their capabilities for eight, ten, and sometimes twelve hours a day.

In addition, most professional athletes have a long break between seasons. After months of competing under extreme pressure, a long off season gives athletes the time they need to rest, heal, renew and grow. But for ordinary people, the “off-season” is limited to a few weeks of vacation per year. And even these weeks they rarely manage to fully devote to rest and recovery - most read and respond to email, exchange SMS and think about work.

Finally, the average career of professional athletes lasts between five and fifteen years. If they manage to organize their finances wisely during this time, they will have enough earned money for the rest of their lives. Very few of them are forced to look for a new job. Ordinary people work for forty to fifty years without significant breaks.

Given these facts, what allows you to work at the highest level of productivity - without sacrificing health, happiness and color in life?

You must work at full capacity. The answer to the challenge of peak performance is to effectively manage all of our energies to achieve our goals. There are four key types of energy. They are at the heart of the change process that we will describe in the following pages, and they are critical to creating the ability to live and work effectively, efficiently and to the fullest.

Principle #1

Full power requires tapping into four interconnected sources of energy: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual.

Man is a complex energy system; To use full power, you need to use all energy sources. You cannot rely on just one of them, and you cannot do without any of them, since they are all deeply connected to each other.

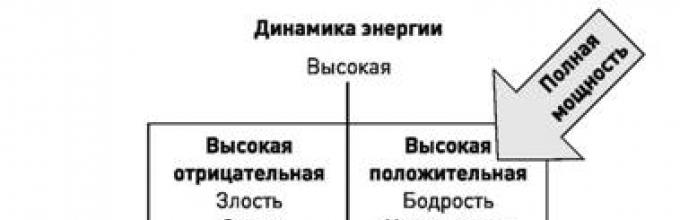

Energy is the common denominator in all aspects of our lives. Physical energy is measured in quantitative terms (high or low), while emotional energy is measured in qualitative terms (positive or negative). These are the two main sources of energy because without enough fuel, no task will be completed. In the diagram we have depicted the change in energy from low to high and from negative to positive. The more “toxic” and unpleasant the energy, the worse it helps to achieve high results - and vice versa.

The importance of full power is most obvious in situations where the consequences of low power can be fatal. Imagine that you are about to have heart surgery. Which of these energy sectors should your surgeon be in? Would you want him to walk into the operating room angry, anxious, and upset? Tired, depressed and exhausted? Or uncollected, complacent and relaxed? Surely you would like him to be energetic, confident and cheerful.

Imagine that every time you get involved in a scandal, do a sloppy job, or can't concentrate on your work, you are putting someone else's life in danger. Very soon you will become more thoughtful about your energy. We must be responsible for how we manage our energy, and this is what we should be rewarded for. And we must learn to manage all types of our energy with equal responsibility: physical, emotional, mental and spiritual.

Principle #2

Since our energy capacity is reduced by both overuse and underuse of energy, we must maintain a balance between energy expenditure and energy storage.

We very rarely think about how much energy we spend, believing that we have endless reserves at our disposal. In fact, if the need for energy grows, then its reserves begin to gradually deplete - especially since the “capacity” of energy sources decreases with age.

By training our ability to manage all types of energy, we can significantly slow down the decline in the physical and mental areas, and even achieve growth in the emotional and spiritual areas. And vice versa - living life “linearly”, that is, spending much more energy than we can store, or storing much more than we can spend, we end up with poor health, chronic fatigue, atrophy, loss of taste for life and even premature death. Unfortunately, the need for restoration is too often seen as a sign of weakness rather than as an important aspect of long-term high performance, and we end up paying little attention to renewing and expanding our energy reserves—both individual and collective.

To maintain a powerful rhythm in our lives, we must learn to expend and renew energy rhythmically. The richest, happiest, most productive lives are characterized by the ability to fully devote ourselves to solving the problems facing us, but at the same time periodically completely disconnect from them and recover. But most of us live our lives as if we were running an endless marathon, pushing ourselves far beyond healthy limits. We maintain a constant level of mental and emotional activity, but we only spend these types of energy without thinking about their restoration. On this path we will face, albeit slow, but inexorable wear and tear.

Think about how many long-distance runners look: tired, exhausted, with dull eyes and sunken cheeks. And what sprinters look like: powerful, agile, impatient - energy literally splashes out of them. The explanation for this is simple. Regardless of how much energy they have to expend, they can already see the finish line from the starting point. We must learn to treat our lives as a series of sprints - giving it our all on the track and completely forgetting about it outside the stadium.

Principle #3

To increase the capacity of our energy reserves, we must go beyond the usual norms of its expenditure, that is, train as systematically as the best athletes do.